Stitch Fix UK Just Highlighted the Personalisation Challenge Facing All Retailers

At-home personal style service Stitch Fix is shuttering its UK business.

I know because I’m one of its customers. In fact, I signed up as soon as the service launched over here in 2019 because I wanted to see for myself how it worked.

Before that my only experience of personal styling was a single in-person session when I was looking for a dress for an evening work event. The stylist was so good at picking options for me that I ended up buying two dresses.

But unlike Stitch Fix, that stylist had me in front of her. She could see everything about my shape, my colouring and even my personal style when I arrived at the appointment. She had me there to provide immediate feedback on colours and styles I did or didn’t like and to physically try on pieces for sizing, comfort and fit.

With Stitch Fix, everything happens remotely. You create a profile with your statistics, budget and any preferences like fabric type – for me, this meant no polyester. Then you book a ‘Fix’ – a box of five items – where you can leave a note for your stylist about what you want and your personal style.

They pick things they think you will like and ship them to you at home to try on. Anything you like you keep and are charged for. Everything else you return. There’s a £10 styling fee, which is credited towards anything you buy, and a discount if you keep all five items.

I still love the concept of Stitch Fix and having a stylist pick out items specifically tailored to me and my style. But its UK departure has highlighted just how big a challenge personalisation is in retail today and why the gap between what consumers say and do may make it impossible.

Why Personalisation is so Hard in Retail

First, I need to say that some of my favourite and most regularly worn items of clothing came from Stitch Fix, including their own labels. When they got it right, they really got it right.

But despite everything the brand knew about me, there were plenty of times where the experience didn’t feel truly personalised for me and my taste. And the truth is Stitch Fix has a lot more concrete data about my likes, dislikes and style than any other retailer I’ve ever shopped with because I was always feeding them.

No other retailer would receive messages from me telling them what I wanted to buy, but Stitch Fix did. No other retailer got detailed feedback on every product I returned and why, but Stitch Fix did. No other retailer had me providing instant thumbs up and thumbs down feedback on outfit and style suggestions on their website, but Stitch Fix did.

So, why couldn’t it deliver me boxes full of clothes that I absolutely loved and couldn’t help but keep – every single time?

For a start, I’m not sure that Stitch Fix ever got a handle on my more ‘edgy’ (yes I hate that term as much as you) personal style despite my best efforts. Email after email would be full of imagery of clothes that had the opposite intended effect – I wasn’t excited to book a Fix.

Part of the problem is that Stitch Fix only allows a maximum number of characters when making requests of stylists or giving feedback on pieces, so it was hard to really communicate what my style is or the sort of items that would fit in with my wardrobe.

When you first sign-up, Stitch Fix asks you to rate a limited selection of 14 different outfit styles as to how much they fit your personal style. But for a service all about personal style, I can’t help but feel that it might have helped to have an onboarding video call instead where a stylist could see how you dress, tour your wardrobe and discuss how you want to look and feel.

In fact, it seems somewhat incredible that the stylists at Stitch Fix never even saw a photo of me.

But this is the fundamental flaw with personalisation in retail today. To truly personalise something is expensive and time consuming. It requires building an ongoing relationship, which doesn’t always pay off. And it’s why defaulting to archetypes and demographics and mass emails is so often the case.

The problem with that is that consumers are weird and complicated and hard to predict. We’re all different from one another, even the people who share similar traits or features or taste as us.

It’s also hard to say whether the data I was providing was truly representative of my style and preferences.

For example, Stitch Fix’s website has a ‘Style Shuffle’ feature which shows images of outfits or items of clothing and asks me to say if it is my style by clicking thumbs up or thumbs down.

While quick and convenient as a gamified communication method, I quickly spotted an issue with the data I was feeding back. When a top that I loved appeared in a pattern I hated, how was I to communicate that? If I gave it a thumbs up was I indicating I liked all elements of that top? If I gave it a thumbs down was I ruining my chances of getting a different top with the same style in my box?

It was the same with the whole outfit suggestions. If I liked the shoes but hated everything else I would give it a thumbs down because I didn’t want the algorithm to throw up suggestions of things I would never wear.

The permanent dilemma about personalisation and customer data is around how good the quality of that data is.

All that data that I said Stitch Fix had about me? Potentially it wasn’t worth very much, which made their job a lot harder.

It’s not just the accuracy of the data though. You also need to be able to make sense of that information to be able to use it. And you also need to consider who is making sense of and using that data – is it artificial intelligence or a human being?

Stitch Fix uses a mix of both in its model just as many other retail businesses increasingly are. The problem is I’m not sure it factored in my inconsistent human nature.

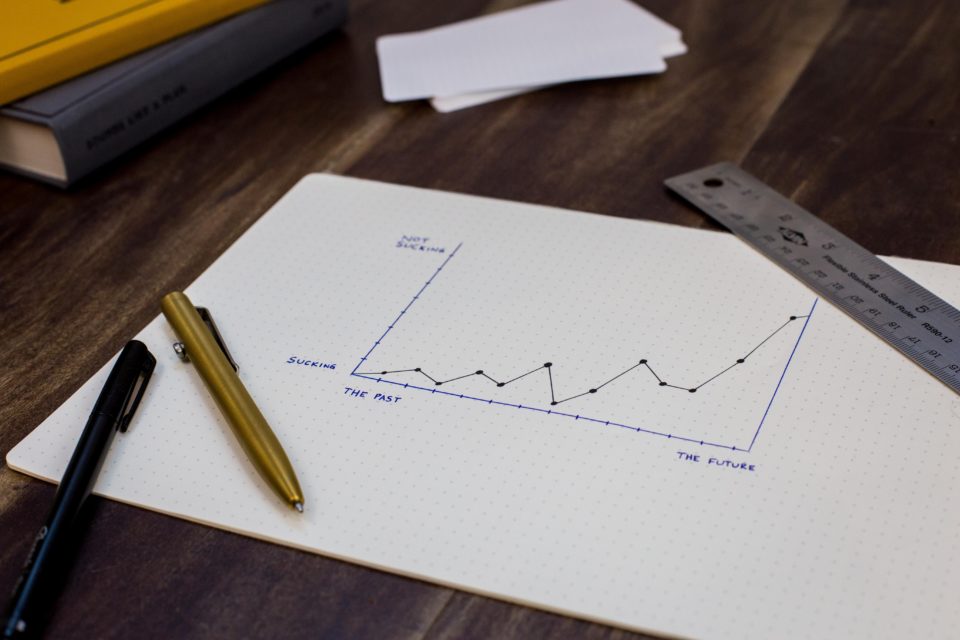

The Problem of the Think, Say, Do Consumer Behaviour Gap

For Stitch Fix, turning my written feedback and requests into concrete guidelines to follow was impossible. Because the truth is sometimes I don’t really know what I really want. Or what I said I wanted went out the window when faced with an alternative.

For example, as far as Stitch Fix’s AI was concerned the only thing I wanted was black clothes because I indicated this over and over again in my profile or feedback on outfit suggestions, as well as the items I actually kept from each Fix.

But then I would add a personal note to my stylist saying that I wanted a pop of colour. All of the data is saying one thing and I’m saying another. How does the stylist reconcile those things in a way that is likely to result in a successful purchase?

The Stitch Fix model constantly had to contend with this gap between what I think and say and what I actually do.

Ideally, Stitch Fix wants its customers to book regular recurring fixes, but I only ever ordered a couple a year. I would tell myself that I didn’t need a monthly box of clothes turning up because I don’t buy new things that often. And, certainly it’s true that I don’t intentionally buy something new every month.

But actually, I’ve realised I buy pieces more often than I think. These unplanned purchases – whether new or second-hand – happen because I see something on social media or when walking through a store, or even because a brand emails me.

The gap between the frequency that I think I shop at and the reality is larger than expected. The problem is that because I had to consciously choose to receive a Fix, Stitch Fix was trapped by my imagined behaviour, rather than benefiting from the reality. And I suspect this is the case for a lot of retailers.

Retailers Need to Consider Consumer Behaviour Within Personalisation

I’m genuinely sad that I no longer have Stitch Fix as part of my retail mix. As I said, when they got it right, they nailed it to the wall – 90% of everything I purchased from a Fix is still in my wardrobe, even the stuff from four years ago. Those pieces have held up over time, continue to work for my style and make me feel good.

Like many shoppers, I’m increasingly conscious about what I buy and how long I keep pieces for. Stitch Fix’s choices fit that criteria.

But of course, operationally Stitch Fix was dealing with some of the most difficult and expensive bits of retailing, namely home delivery and returns, and all offered for free. The cost of them not getting it right was particularly high as entire Fix’s could be returned if I didn’t like the contents.

More than that though, Stitch Fix had all the hard parts of personalisation and consumer behaviour to contend with.

With more and more retailers reporting plans to invest in personalisation, it’s never been more vital for them to get their heads around how that actually works in the reality of consumer behaviour.

Because it may be that our fickle nature will never allow for true personalisation – at least not if it’s relying too hard on past data and our own conceptions of what we want.

We’ve already seen this happen in the grocery industry where online basket recommendations and quick reordering based on past purchases are meant to offer convenience but instead leave customers bored.

Personalisation needs to be based on a fuller picture of an individual. Ideally, it needs to be based on a genuine relationship between the brand and the customer. Because only then can retailers understand that customers want to be inspired and discover new things that feel true to their tastes and preferences. Occasionally, they want to be challenged on those preferences but in a thoughtful way.

Remember I said that I bought two dresses during an in-person styling session some years back? Neither of them were black. But if you had asked me ahead of time, black is what I would have had in mind because of the look that I like.

So why did I end up with something else entirely? Because those dresses were still undeniably in keeping with my style. They represented who I am and how I like to present myself to the world. And I still have both in my wardrobe to this day.

Want more consumer behaviour insights? Talk to us about a bespoke report that digs down into what your customers may be saying and what they’re actually doing.